Release Date: May 07, 2013

The Folks Who Live On The Hill

Lush Life

Stop This Train

Adagio

Easy Living

Doll Is Mine

Infant Eyes

Let It Be

Final Hour

Last Glimpse Of Gotham

Stardust

Let Me Down Easy

Players:

Joshua Redman (saxophone), Brad Mehldau (piano), Larry Grenadier (bass), Brian Blade (drums), Laura Frautschi (concertmistress), Avril Brown, Christina Courtin, Karen Karlsrud, Ann Leathers, Katherine Livolsi-Landau, Joanna Maurer, Courtney Orlando, Yuri Vodovos (violin,) Vincent Lionti, Daniel Panner, Dov Scheindlin (viola,) Stephanie Cummins, Eugene Moye, Ellen Westermann (cello,) Timothy Cobb (bass,) Pamela Sklar (flute,) Robert Carlisle (french horn), Conducted by Dan Coleman.

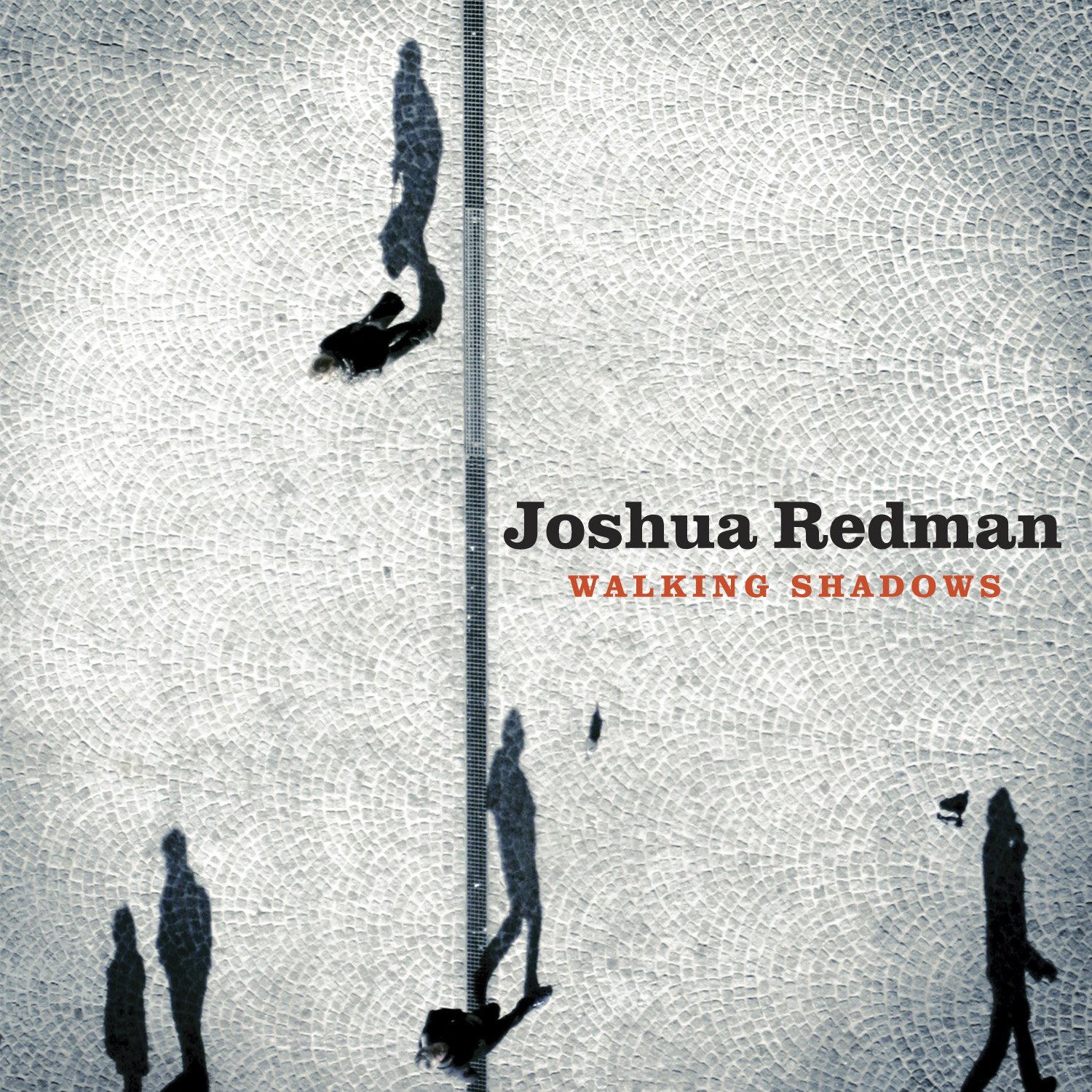

Walking Shadows

Creating his own take on the classic jazz-with-strings album was the initial impetus for Joshua Redman’s Walking Shadows, a collection of ballads, both vintage and contemporary, that can be as eloquently moody and restless in feel as they are hauntingly beautiful and serene. With his friend and frequent collaborator, the pianist Brad Mehldau, on board as producer—the first time Mehldau has assumed that role for a project other than one of his own—Redman has retooled a familiar formula. The jazz-with-strings concept serves as a starting point, as foundation and inspiration, for Redman’s exploration of an ambitiously eclectic set of tunes performed in a variety of configurations. The strings themselves are an active, emotive presence on the six songs in which they are featured and their absence on other tracks only seems to heighten the drama of those more austerely arranged compositions.

Redman and Mehldau culled material from the best of the Great American Songbook, including “Easy Living,” “Lush Life,” “Stardust,” and “The Folks Who Live on the Hill.” But they also looked much further afield, reframing pieces from J.S. Bach (the Adagio from his organ Toccata in C) to the Beatles (“Let It Be”), from a soulful John Mayer number (“Stop This Train”) to the angular rock of New York indie stalwarts Blonde Redhead (“Doll Is Mine”), plus a few original tracks from Redman and Mehldau. While the songs required an individualized approach, Redman and Mehldau managed to artfully fit them all together to form a kind of seamless narrative, an often brooding and melancholic one that seems to unfold, as the Macbeth-derived album title suggests, between the light and the dark.

“The strings add a richness and a lushness, a romanticism and even a touch of nostalgia to the music,” explains Redman. “But we also wanted that to be balanced with an intimacy and a directness and a rawness, so as we started to think about the different tunes, we also thought about the different possible configurations for them. There are six songs with strings, but two of them don’t have the rhythm section. And there are quartet songs, a couple of trio songs (one without bass, one without piano), a duo song. We tried to explore a variety of instrumentation and texture in the course of making the record.”

Redman cut Walking Shadows last September at Avatar in Manhattan with Mehldau on piano, longtime friends and collaborators Larry Grenadier and Brian Blade on bass and drums, and 15 orchestral players. James Farber engineered and Dan Coleman, who had previously worked with Mehldau on his 2010 Highway Rider release, served as conductor. Along with Mehldau, Coleman contributed string arrangements, as did composer Patrick Zimmerli, who’d written and arranged for Mehldau’s 2011 Modern Music duo-piano disc. The tracks were recorded live in the studio, the string parts included, making for an exciting, albeit high stakes, session that required both great attention to detail and plenty of improvisatory daring.

Key to the recording, says Redman, “was trying to make sure we preserved that sense of spontaneity and interactivity and conversation and surprise which is at the core of great small-group jazz, even in contexts where we were playing along with this larger ensemble with strings. That was part of our job: to help make the orchestra sound as if it were genuinely a part of the improvisation and conversation, of the ebb and flow, of the give and take, even though, of course, the strings themselves weren’t really improvising at all. It’s one of the reasons it was so important for us to record everything live, with the strings at the same time, as opposed to recording them in a session as an overdub, which might have been technically and logistically a lot easier. But musically, I think that would have made everything feel less natural and integrated. And Brad, Larry, and Brian are all geniuses in that respect. They just instinctively know how to be completely open, free, and interactive in the moment, but at the same time be fully aware of the larger context in which they’re playing, and conscious of the overall texture and structure. Above all, they’re always mindful of how everything is contributing to the development and interpretation of the song.”

In 1998, Redman and these same players cut a well-received ballads set as a quartet called Timeless Tales (For Changing Times), a then-meets-now effort that juxtaposed standards with repertoire from the likes of Prince, Joni Mitchell, and Bob Dylan. In the 15 years since, Redman has developed a deeper appreciation for the songwriter’s craft, for the words as well as the music: “I did reference the lyrics to many of those Timeless Tales songs, but I don’t think I let most of them sink in as much as I did with this project. With Walking Shadows, my relationship with the lyrics was much more immersive. And, in many cases, it actually helped to determine which songs we might play and how we might play them.”

Mehldau had brought up the possibility of cutting John Mayer’s “Stop This Train.” As he recounts, “Josh has such a way of getting at the heart of a song, and this is a really great song. It has the kind of Beatles harmony that I know is already part of his sensibility, so I knew that it wouldn’t be a stretch for him.” In its original form, “Stop This Train” was a sweetly boyish complaint about the inevitability of growing up (and old). Redman’s expressive lead lends it more truly adult sensibility. Continues Mehldau, “What I love about Josh’s performance is the way he brought the blues into this kind of world in the figuration he plays around the melody as it builds intensity. He took the song and made it jazz.”

Redman himself contributed perhaps the most left-field idea, Blonde Redhead’s “Doll Is Mine,” which he originally heard via his James Farm band mates: “I never really imagined I’d play one of their songs, especially not in this context—for a jazz ballads record. My concept was to take the song and slow it down a lot, playing it almost like an old school soul ballad, but at the rehearsal Brian Blade came up with a totally different approach to the drum beat—something much more fluid, nuanced and subtle. It was so much better than my concept, though it took me a few takes in the studio to actually realize it. After the session, Brad and I were listening and evaluating and we realized that ‘Doll Is Mine’ really had something unique in terms of atmosphere and groove—very relaxed yet forward-moving, with natural heartfelt, melancholic bluesy expression.”

Redman also guided the pop benediction of Paul McCartney’s “Let It Be” to a surprising place: “I had this vision of almost playing it like a country gospel song, a very simple, relaxed approach, with a little bluesy tinge but a plainspoken directness. And that’s how we approached the main melody. But then there is the tag where it gets more extroverted and agitated, where it starts to really take off. It becomes the most hard-hitting small-group playing on the record. I liked that contrast. I also feel it relates to a possible lyrical irony imbedded in the song. The lyrics of the first verse are obviously about being peaceful, about finding solace and comfort in the midst of anxiety and trouble, about accepting things. We play the song in that way at first; but the vamp at the end is resisting that. There’s a tension, a refusal to let things be as they are, a striving or longing for a better world, that perhaps refers to the more idealistic, protest vibe implicit in the second verse. We’re playing with messages, with lyrics.”

In other cases, the strings were very much part of the transformative process, supplying a real voice of their own throughout. Redman says, “We wanted them to feel essential, not incidental, to the music. They needed to be a critical part of the interpretation, of the musical conversation. For example, the verse to ‘Lush Life’”—arranged by Zimmerli—“has very active and prominent strings; they’re playing key melodic figures. Actually, Patrick kind of wrote that section so that it would sometimes sound like certain strings were ‘improvising’ counter-lines against my pretty straightforward statement of the verse melody. On the other hand, with a song like ‘Let Me Down Easy’,” the Redman original that serves as the album’s melancholic denouement, “the role of the strings feels maybe a bit more supportive and atmospheric with respect to the way Brad, Larry, Brian, and I are playing.”

Dan Coleman’s arrangement of Wayne Shorter’s “Infant Eyes,” on which Redman switches from tenor to soprano sax, perhaps falls somewhere in between: “I think in some ways the melodic voice of the orchestra on that song might be enhanced by my improvisational approach. At times, I’m really trying to listen to and interact with the strings, taking some of the ideas they throw out there and responding to them and elaborating on them, using them as the basis for further improvisation. The rhythm section is right in there with me, doing the same thing, so overall it has a very conversational and interactive feel.”

Jazz-with-strings is a sub-genre that has produced such milestones as Charlie Parker With Strings, Stan Getz’s Focus, and Art Pepper’s Winter Moon. Redman cites works by Clifford Brown, Ben Webster, and Wynton Marsalis among his personal favorites, as well as the vocal jazz recordings of Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan, Frank Sinatra, and Nat Cole. But it was after participating in Mehldau’s Highway Rider sessions, and accompanying Mehldau on tour following the double-disc’s release, that his interest was seriously piqued to work in an orchestral setting—and he knew he had to get Mehldau involved if he was going to do it: “I relate so strongly to his aesthetic and we connect on so many levels. There’s really no one I could have trusted more—especially for a project like this, with all the work that had to be done and all the decisions that had to be made, and with finding an honest and interesting and hopefully compelling way to integrate these two worlds—the world of improvised jazz and the world of orchestrated strings.”

For this pair of old friends, the process didn’t end at the tracking session’s conclusion. Finding the right placement for the strings, defining their role within the overall mix, was their final, and perhaps most crucial, task. Explains Redman, “This was something we spent a lot of time working on and trying to make sure we got right for each song. I think James Farber, our engineer, really did a brilliant job in that respect. And we had a really great working vibe at the mix with him and Brad and me listening, evaluating, discussing and finally making the ‘right’ decisions. We had our general concepts and our assumptions and our philosophies. But we really had to feel everything out on a case-by-case, song-by-song basis. So much depended not only on the particular song and the particular arrangement, but also sometimes on the particular vibe of the particular take we might have chosen. In the end, though, I think we were striving for something that felt natural. We wanted the final mixes to be warm and lush and enveloping, even comforting—after all, it is, essentially, a ballads album. But I think we also didn’t necessarily want any aspects of the sonics or the production to call too much attention to themselves. We wanted to highlight the music, not the technique. We’d rather people come away thinking ‘this music feels good’ as opposed to just ‘this record sounds great.’”

—Michael Hill