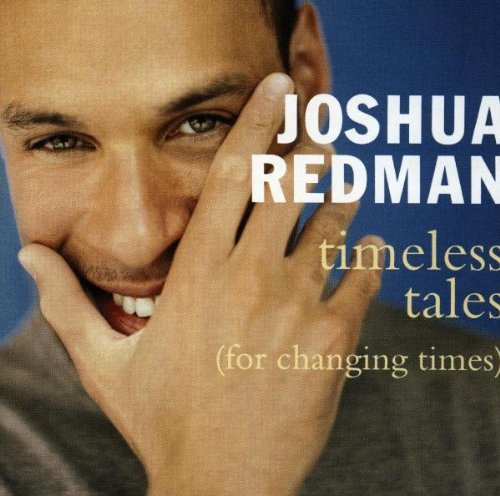

timeless tales

Release Date: September 18, 1998

-

There is the song which tells you a story. It puts you in a mood. It takes you on a journey. It paints you a picture. It sets the scene. It develops the characters. It scripts the dialogue. It stages the plot. And if it is good – if it is artfully constructed, thoroughly rehearsed, and meticulously executed, if it pushes all the right buttons – it achieves a keen and commanding impact. It gives you a strong feeling. It enchants you, it excites you, and it entertains you. But the feeling is fleeting. The impact is temporary. The story, affecting as it may be, still belongs to a particular time, place, stylistic phase, and cultural space. It is over-written, perishable by virtue of its own literalness. The song is dated. It is destined for nostalgia. No matter how much the song initially moves you; eventually, sooner or later, you move on. And when you do, you leave that song behind.

Then there is the song which inspires a story that you yourself can tell. This song asks you how you feel. It lets you guide it where you want to go. It provides a canvas, a color palette, maybe even a preliminary sketch; but it gives you the paintbrush. It builds the scene around you. Its characters are your familiar friends (and enemies). They speak a dialect that you full understand. You are an integral part of the action. The story leaves plenty of room for your own singular imagination. It involves you. It not only tolerates, but in fact demands, your vigorous participation. And if it is good – if it is powerful, if it is inventive, if it is seductive – then the emotional experience is all the more profound, because you have been so instrumental in its creation. The impact is lasting because it has been conditioned and fortified from within. The story has permanence because it flows through you, wherever you are, whenever you tell it. The song is forever. It is timeless. It is always with you, because (as Hammerstein and Kern so aptly put it) “the song is you.”

It is this song which the jazz musician seeks. The jazz musician is not just looking for a song to play; she is looking for a song to play with. She is not just searching for material to perform; she is searching for material to interpret. The song which attracts the jazz musician is the song of ageless beauty and infinite possibility. It is the song which asks as much as it answers, which suggests much more than it decides. For the jazz musician, it if never enough that a song tells a good story. Because for the jazz musician, it is not the story but rather the act of storytelling itself which holds the highest value and offers the greatest inspiration.

The jazz musician wants to tell his own story; and what’s more, he wants to tell it differently every time. The general setting may be preserved. The central protagonists may remain intact. But the plot always unfolds differently. The substance (if not the style) of the dialogue varies dramatically. And the outcome is never predictable. The jazz musician is an improviser; and an improviser is a spontaneous storyteller who writes the script in the very same moments that he enacts it. His material should be broad, open-ended, an interpretable. The jazz musician tries to take a song written yesterday and play it as if it were meant for tomorrow. So the song which the jazz musician takes should be relevant. It should be universal. It should be timeless.

Each of the songs on this recording was written with the last one hundred years. Each was written by a well-known and well-respected songwriter of his or her era. Each was well-received in its time. Five of the songs come from the “classic” period of popular songwriting, centered around the Tin Pan Alley and Broadway showtune traditions. Five come from the “modern” period of popular songwriting, dominated by the R&B, rock, folk, and soul movements of more recent years. All of the composers wrote their lyrics in English and worked within a distinctly Western musical idiom.

Considered in this manner, this recording could probably qualify as a “concept album.” It is a jazz celebration of twentieth century Western popular song. But it is a celebration without nostalgia. The purpose of this recording is not to look back dreamily and longingly at the “golden ages” of our musical past. The idea is not to recreate the styles, circumstances, and conventions which defined the original versions of these songs. The goal is not to prove, through slavish imitation and faithful reproduction, how important these songs were. Rather, the concept of this album is to express, through contemporary treatment and personalized interpretation, just how relevant these songs still are – even now, in this insecure, impatient, and instable culture of the millennium.

All of these songs are (in my humble estimation) wonderfully timeless. They evoke moods, settings, sensibilities, and experiences of universal human significance. They speak in a variety of ways to a diversity of ears, on a multiplicity of levels. They provide the emotional substance and spiritual depth which inspire and sustain musical creativity. They intimate remarkably poignant and subtly complex meanings.

And they all mean a great deal to me. These songs don’t just move me as a listener; they engage me as a player, improviser, arrangers and bandleader. I find in them a wealth of raw material which I attempt to assemble, fashion, and transform according to my own gradually emerging aesthetic. These songs attract me. They interest me. They involve me. Their melodies, harmonies, rhythms, and lyric resonate powerfully and sympathetically with the signature sounds of my own soul.

Moreover, these songs, treated in these ways, have great meaning for this band. They (please excuse the pun) “strike a chord” with all of us, as a group. We try to integrate them, naturally and seamlessly, with our evolving ensemble sound. They are catalysts of mutual inspiration and axes of collective identity. In them, we hope to discover and develop a common musical voice. Through them, we seek to articulate a shared artistic vision.

And that, much more than the “great songs of the century” concept is what this recording is really all about. It’s about individual and collective affinity. These songs speak to us and they give us something to say. Their stories have been told many times, over many years, in many different forms; and yet I still believe there is something unique which this band and these arrangements contribute to their telling. I hope we have been able to convey something distinctively modern with these songs, while still imparting some of their essential, eternal meanings.

This album is not an anthology. This collection of songs is no definitive, or even representative. Instead it is a highly subjective and (like most things subjective) somewhat arbitrary offering. I am not parading these songs as the finest of the century, nor am I proclaiming their composers to be the most important. I have chosen these songs simply because I like them, because I want to play them, and because I feel I have something original to express by interpreting them. They’re just ten great songs, written by ten great songwriters. Ten great songs, resilient enough to change with the times and with the artists who change them. Ten timeless tales, universal enough to have enduring cultural relevance and beautiful enough to have profound personal resonance – not just for us improvising jazz musicians, but hopefully for you imaginative jazz listeners as well.

—Joshua Redman June, 1998

-

On his sixth album, Joshua Redman celebrated the full range of 20th-century popular song, from Tin Pan Alley legends Cole Porter, the Gershwins, Irving Berlin, and Rogers & Hammerstein to modern-day greats Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell, Stevie Wonder and Prince. With this intriguing breadth of repertoire and Redman's customary passion and virtuosity, Timeless Tales (For Changing Times) is a stunning collection of modern standards interpreted by one of the preeminent figures in contemporary jazz.

Performed with longtime collaborators Brad Mehldau, Larry Grenadier, and Brian Blade, Joshua's arrangements reinvent these songs through a number of exciting and varied approaches, transforming the familiar into the refreshingly new.

In the album's liner notes, Joshua wrote, "These songs don't just move me as a listener; they engage me as a player, improviser, arranger, and bandleader. They're just ten great songs, written by ten great songwriters. Ten great songs, resilient enough to change with the times and with the artists who change them. Ten timeless tales, universal enough to have enduring cultural relevance and beautiful enough to have profound personal resonance - not just for us improvising jazz musicians, but hopefully for you imaginative jazz listeners as well."

-

Joshua Redman (saxophones),Brad Mehldau (piano), Larry Grenadier (bass), Brian Blade (drums)