Release Date: September 20, 1996

Hide And Seek

One Shining Soul

Streams Of Consciousness

When The Sun Comes Down

Home Fries

Invocation

Dare I Ask?

Cat Battles

Pantomime

Can't Dance

Players:

Joshua Redman (saxophones), Peter Bernstein (guitar), Peter Martin (piano), Christopher Thomas (bass), Brian Blade (drums)

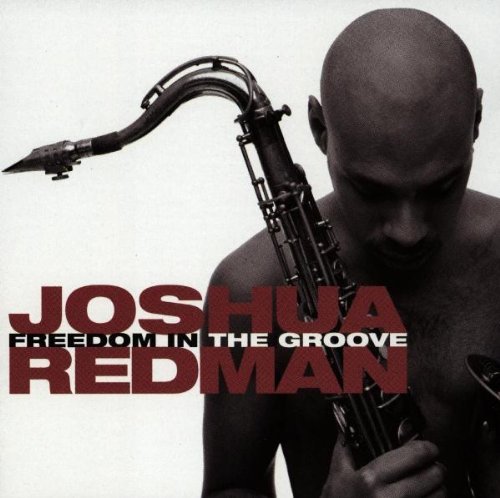

Freedom In The Groove

An artist fully committed to deepening his sound and exploring his potential, Joshua Redman unveiled an expanded band, a new horn, and some infectious, funk-inflected rhythms on 1996's Freedom in the Groove, his fifth album for Warner Bros.

"One thing I've discovered about myself," Redman said, "is that I'm an eclectic as a person and as a musician. I grew up listening to and loving all kinds of music, and that variety and diversity are in my soul. For me, this album represents an extension of the soul and spirit of jazz improvisation - interaction and spontaneity - into territory that isn't conventionally considered part of the jazz idiom."

To take on this challenge, Joshua expanded his usual quartet with the addition of guitarist Peter Bernstein, well-known for his work with Larry Goldings and Lou Donaldson. "Having a guitar in the band was crucial to exploring this territory," Joshua emphasized. "Another instrument allows you to flesh out your voice compositionally, and a guitar is much more flexible than a more traditional quintet instrument." Bernstein's ability to fit seamlessly into Redman's concept is one of the album's defining traits, from the rock-solid tenor/guitar phrasing of "Home Fries" and the conversational exchanges on "One Shining Soul" to the flexible lead-shifting of "When the Sun Comes Down" and the rhythmic and melodic layering of "Cat Battles."

Amidst the other changes heard on Freedom in the Groove, Redman also made his debut as an alto saxophonist on "Invocation" and "Can't Dance." With his soprano (heard on "One Shining Soul" and "Pantomime") and trademark tenor also at hand - Joshua proved himself not only a formidable triple-sax threat, but as usual, a musician of rare emotion and unsurpassed taste.

LINER NOTES

When I first heard jazz, it wasn’t “jazz.” It was music. I grew up in a household where you could hear Ornette Coleman right next to Otis Redding, where A Love Supreme and Sergeant Peppers were both in heavy rotation, where Old and New Dreams and a Balinese Gamelan Orchestra often shared the same bill. When I was young, I didn’t recognize “jazz” as being categorically separate or substantively different from “blues,” “rock,” “funk,” “soul,” “classical,” “Indian,” “African,” “Indonesian,” or any other of the countless musical genres I heard piping over the public airwaves or crackling out of my mom’s old reel-to-reel tape recorder. I wasn’t yet conscious of musical styles as well-defined, easily-labeled, intellectually-specific entities. For the most part, I didn’t even know their names.

Of course, like any attentive listener (of any age), I could sense emotional contrasts, personal singularities, and group identities. I could perceive the specialness of each record, the originality of each band, the distinctness of each song. I could feel the undeniable, intangible qualities which gave each artist his or her unique, inimitable sound. But I could also appreciate the kinships and the similarities, both within and across stylistic boundaries. And I could hear more than just a little in common between the volatile beauty of Sonny Rollins’ phrasing and the explosive unity of Senegalese drumming; between the yearning flights of John Coltrane’s soprano saxophone and the soaring cries of Bismillah Kahn’s shanai; between the fully flowing warmth of Cannonball Adderley’s tone and the effortlessly embracing depth of Aretha Franklin’s voice. It all made sense. It all felt right. It was all music.

Naturally, as I grew older and more knowledgeable, I became increasingly conscious of “jazz” as a distinct musical genre. I learned the significance of the flattened fifth. I apprehended the technical nuances of swing rhythms. And perhaps most importantly, I recognized the unconquerable challenge and the unsurpassable fulfillment of improvisation – that creative, liberating discipline which gives jazz its immediacy, its potency, its soul. I became increasingly interested in, and enamored with, jazz. As a musician, jazz became my style of specialty. As a listener, jazz because my music of choice.

At one point, during my first few years of college, I even became what some folks might describe as a “jazz snob.” I locked myself in my dorm room and wore down the grooves of my Blue Note reissues while my vintage Motowns sat in a box collecting dust. I derided my roommates’ heavy metal as mindless, simplistic noise. I listened to hip-hop for the sake of social recreation (dancing, hanging, partying). I accepted classic rock out of academic necessity (you couldn’t walk across campus on a sunny day without hearing at least two of The Who’s greatest hits). But I craved, studied, adored, and respected jazz. Jazz was serious music. Jazz was my favorite music. Jazz was The Music.

Those were my attitudes at that time, and I am not ashamed for having once possessed them; (just as now I am not ashamed to say that I love Stevie Wonder’s Inner Visions as much as I love Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue.) They belonged to a natural (and probably even a necessary) phase in my development as both a listener and a player. By focusing on jazz to the exclusion of other styles, I cultivated a much greater appreciation of a truly great art form. I developed a deeper understanding of an incredibly subtle and complex aesthetic. I became fully aware of the specialness of “jazz.”

But now is a different time, and I am in a different place. Without a doubt, I still adore jazz; I still need jazz; and I am still at a very elementary stage in what I am sure will be a lifelong, never-ending study of the jazz idiom. As a class, I admire the great jazz musicians of the 20th century as much as (if not more than) any other group of artists throughout modern history. And if I had to pick one and only one style of music as my absolute, exclusive favorite – one style to be trapped with for the rest of my life on a remote, inescapable desert island – I would still pick jazz.

But fortunately, I don’t. Art, in the world of honest emotional experience, is never about absolutes, or favorites, or hierarchies, or “number ones.” The “desert island” scenario is wholly irrelevant to real-life tastes, choices, and attitudes. These days, I listen to, love, and am inspired by all forms of music. And once again. I sense the connections. I feel in much of ’90s hip-hop a bounce, a vitality, and a rhythmic infectiousness which I have always felt in the bebop of the ’40s and ’50s. I hear in some of today’s “alternative music” a rawness, an edge, and a haunting insistence which echoes the intense modalism and stinging iconoclasm of the ’60s avant-garde.

I watch MTV, and I enjoy it. Sometimes I even respect it. I’ve dusted off those old Motown sides and mixed them all up with the Blue Note classics. I just called my mom and asked her to send me a copy of that Bismillah Kahn. On a good day my CD rack is organized alphabetically, but never categorically. I’ve got it all in heavy rotation. They’re all sharing the same bill.

I feel as if I am returning to the open-minded, wide-eared sensibilities of my early years, without abandoning the aesthetic knowledge which I later acquired.

I listen with stylistic innocence as well as critical intelligence.

I identify genres but ignore their limits.

I preserve my roots as I extend my branches.

Coming from a tradition but walking toward the horizons.

It takes me on a journey while it keeps me close to home.

Focused and eclectic: specialization and inclusion can go hand-in-hand.

Put it in the pocket, but keep it on the edge.

Give me a naked soul and a mature mind.

You can be grounded yet still be free.

With a swing. In the groove.

Playing jazz.

Playing music.

—Joshua Redman June, 1996