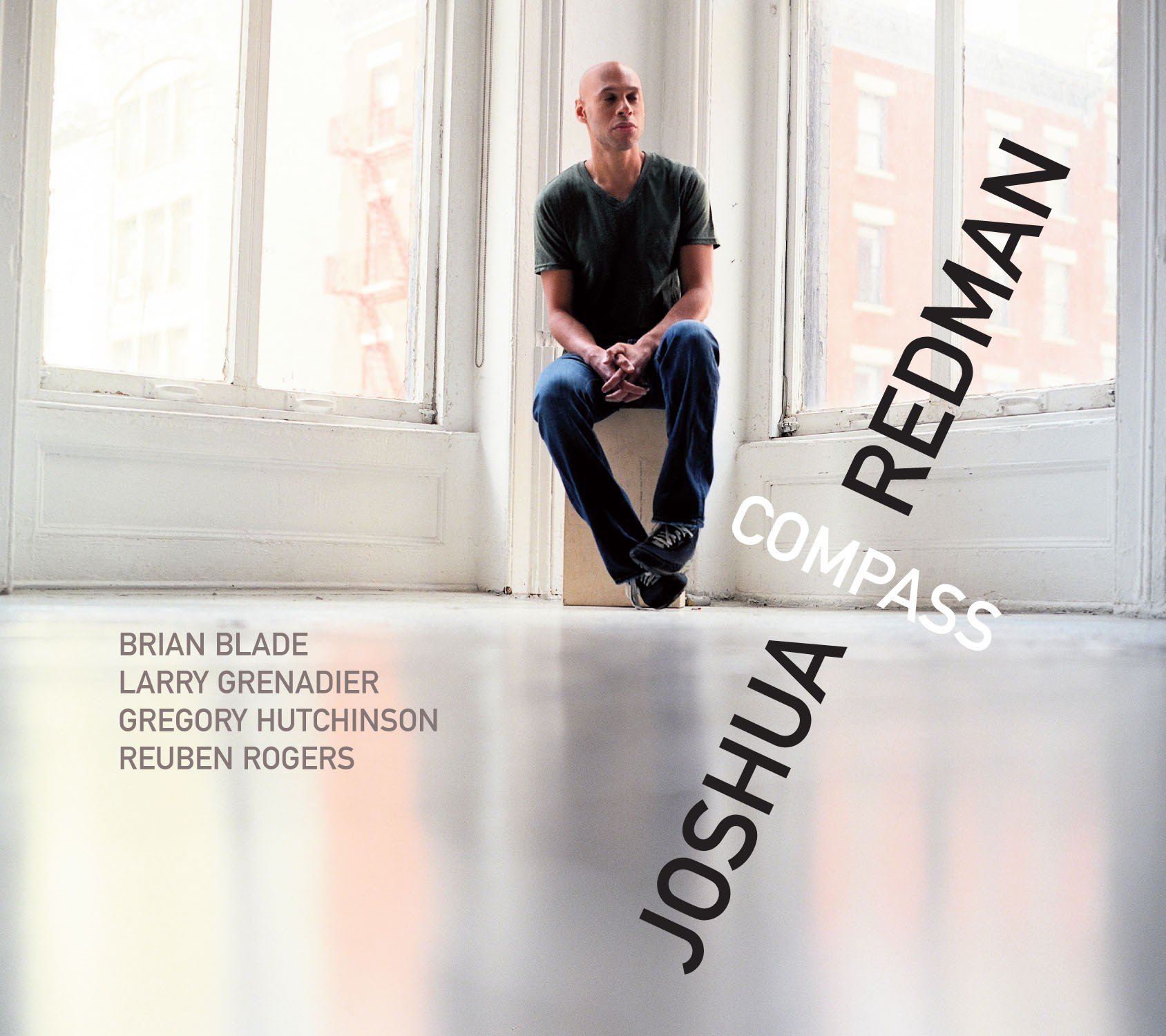

Release Date: January 13, 2009

Uncharted

Faraway

Identity Thief

Just Like You

Hutchhikers Guide

Ghost

Insomnomaniac

Moonlight

Un Peu Fou

March

Round Reuben

Little Ditty

Through The Valley

Players:

Joshua Redman (saxophones), Larry Grenadier (bass), Reuben Rogers (bass), Brian Blade (drums), Gregory Hutchinson (drums)

compass

On Compass, Joshua Redman takes the concept of “playing trio” in surprising new directions. The title of his third Nonesuch disc evokes navigation, travel, a desire to find one’s bearings. Redman confirms, “This album was a journey for me, a further exploration of the trio format. Musically, it’s an expansion on, and extension of, Back East,” his acclaimed 2007 set and his first studio recording with an acoustic trio. Now, with a group of collaborators as intrepid as he is – bassists Larry Grenadier and Rueben Rogers, and drummers Brian Blade and Gregory Hutchinson – Redman literally and figuratively stretches the shape of the trio approach; on the most audacious of these tunes, he performs with the entire lineup in a double-trio setting.

The saxophonist recorded Compass during three days in March ‘08 at Avatar Studio in New York City, and it was a bracing leap into the unknown for him. As Redman admits, with a laugh, “Sometimes I’m guilty, with my recordings, of having too clear a plan. This time I said, ‘Hey, I just have to let go.’ If I try to plan it, it’s not going to work, so I’ll just think about some tunes that we could do with everybody together, we’ll get in the studio and see how it goes. There was a real kind of release for me with this project, an embrace of the unfamiliar.”

Redman conceived the album as he toured throughout ‘07 in support of Back East, which the New York Times has called “the most agile and personal record of his career,” one that pays homage to his forebears, in particular Sonny Rollins, while displaying Redman’s own considerable gifts as composer and arranger. As Redman explains, “There are some originals on Back East, but a lot of the tracks were my arrangements of other people’s tunes. So once we got out there and started playing as a trio, I was inspired to write a lot more. Initially, my idea was to just find one trio, one drummer and one bassist, and really try to focus in on that rhythm section, on one group sound. I’d record some of these tunes and that would be it. But as I continued to tour, I had the opportunity to play over an extended period of time with a lot of different rhythm section combinations. At a certain point, I thought it might be interesting to mix it up a bit with this session: take two of my favorite bassists and two of my favorite drummers and try a ‘musical chairs’ kind of thing -- paring each bassist with each drummer and recording in each of the four possible bass-drum combinations.”

“I guess it was a couple of months before the date,” he continues, “when it dawned on me: what would it be like with multiple bassists and drummers? What would it be like to do something with everybody in the room together? Common sense was telling me to stay away, that it had the makings of a big mess. All that bass and drums could end up sounding muddy, clumsy, directionless, unfocused. But my imagination kept leading me back to this idea, and, at a certain point I decided it was worth a try. Why not do it, schedule a day, and see what happens, with no expectations?”

The result is an album that offers, especially on the double-trio tracks, a palpable sense of the physical and creative atmosphere as the players interacted. Redman and James Farber, the engineer and co-producer of the date, place the musicians in the album mix exactly as they were positioned in the studio, with one drummer on the far left, another on the far right and the two bassists closer to the middle. “Identity Thief,” the first of the double-trio tracks, starts off unhurriedly, with Redman’s tenor sax serving as a kind of alarm clock to the twin rhythms sections, which eventually work themselves up to a propulsive jam. If you put on a good set of headphones, or crank the volume on an old-school stereo, you can follow the action as it vividly unfolds: That’s Grenadier’s bass shadowing Redman’s line close on the left, Hutchinson weighs in on the right with a brief percussive flourish, echoed shortly thereafter by Blade, back on the left. Says Redman, “We really tried to capture that sense of sound in space, where every instrument has its place in the sonic landscape. The first day of the session, we all played together, and I think that established a kind of unity for the group, a sense of continuity for everything that happened after that.”

Though the ensemble displays an easy-going swing on tracks like “Round Rueben” and “Hutchhiker’s Guide,” much of Compass has a brooding, ruminative quality. The opening cut “Uncharted” sets the tone. Says Redman, “’Uncharted’ is not a typical first tune for an album, it doesn’t announce itself as a lot of tunes will. There’s an ethereal mood but also an unsettled quality. Basically, this is a completely free tune; we started playing and we’re all just kind of searching. Whatever harmony we discover is by chance, each of us is floating and finding our way, listening to each other. And that was one of the reasons I wanted to have it start off the album. With this whole project, there was a sense of embarking on a journey for which we didn’t have a clear or detailed map. We had to rely on our collective intuition, our own internal compass, if you will.”

Though Redman himself undertook most of the composing, he did ask his fellow players to bring in songs or sketches; Grenadier’s “March” is represented on the album, as well as Blade’s “Through the Valley.” Redman also wrote an arrangement for double trio of the first movement of Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata,” a song that fits in right at the center of Compass with its sublimely melancholic feel. Redman explains, “I have very little familiarity with classical music, but I’ve always been drawn to this piece. There’s nothing really repetitive about the harmony; and that’s one of the wonderful things about classical music and one of Beethoven’s great gifts. With jazz, a lot of times you have a tune with a series of chord changes that repeat over and over. But here you have this extended, patient but dramatic, almost epic, progression, which, quite frankly, is heart-wrenching to me at times. Through it, Beethoven creates so much beauty, gravity and emotion.”

Redman has put a lot of himself into these tracks; in the depths of its grooves, Compass reflects “a kind of very personal, psychological, maybe even spiritual, struggle. In a lot of ways, over the last couple of years, things have been the most peaceful, content and happiest for me. In terms of what’s going on in, and around, my life, everything feels good and right. But the bizarre thing is that, at the same time, I’ve been experiencing some intangible, but very real, trouble from deep within -- confusion, anxiety, frustration, self-confrontation. Much of this inner drama was unfolding while I was writing this music, and even more so in the months leading up to the recording. So there was this sense of an internal journey, of trying to orient myself, find my bearings, navigate through the land mines of my own psyche.”

One of several meanings of the remarkably versatile word “compass,” Redman points out, is an archaic verb form synonymous with “to accomplish.” He concludes, “I do have a sense of fulfillment with this recording. I feel like we may have discovered something in our musical travels, perhaps even arrived somewhere: We placed ourselves in an unfamiliar, untested musical context, and relied on our instincts, camaraderie and shared aesthetic values to create music which we hope feels honest, heartfelt and spontaneous.